As reported recently in the Vancouver Sun, Vancouver’s push to add “missing middle” housing has recently run into a serious obstacle: at least nine multiplex projects have been halted after being built too close to high-voltage power lines. According to city officials, accredited professionals signed off on designs that failed to meet clearance requirements, creating significant risks for both workers and future occupants. Stop-work orders have been issued by both the City of Vancouver and WorkSafeBC, underscoring the gravity of the situation.

The Code at the Core of the Issue

The Canadian Electrical Code (CEC), Clause 36-110, outlines mandatory separation distances between buildings and high-voltage lines. Specifically, Tables 32 through 34 provide detailed clearance values that vary based on voltage, location, and the type of surface workers may access. These tables are not optional—they form the baseline for safe and compliant design.

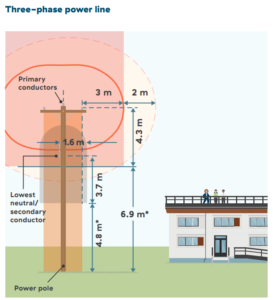

How these requirements are interpreted and applied often depends on the local authority. For instance, Table 33 of the Canadian Electrical Code defines horizontal clearance to adjacent structures, while Table 32 addresses vertical and radial clearance to unguarded high-voltage equipment. A single-storey garage might technically comply if it maintains the required vertical clearance, even if a nearby HV line encroaches slightly within the 3-metre horizontal distance. But replace that garage with a two-storey laneway house on the same footprint, and the structure would almost certainly fall out of compliance. To manage these grey areas, Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJs) frequently lean on BC Hydro’s guideline, “Guide to Utility Clearance Requirements,” (see figure titled “Three-phase power line”) which adds utility-specific standards on top of the CEC. Municipal permitting systems often defer to professionals—engineers, architects, and electrical contractors—to certify compliance. Yet as recent stop-work orders illustrate, even small errors in judgment at this stage can lead to costly and disruptive consequences.

Why WorkSafeBC is Involved

Beyond the static clearance requirements of the CEC and BC Hydro guidelines, WorkSafeBC regulations introduce the concept of “general limits of approach.” These rules ensure that workers maintain safe distances from energized equipment not just at the time of occupancy(“Day 0”) but throughout the lifecycle of the building.

requirements of the CEC and BC Hydro guidelines, WorkSafeBC regulations introduce the concept of “general limits of approach.” These rules ensure that workers maintain safe distances from energized equipment not just at the time of occupancy(“Day 0”) but throughout the lifecycle of the building.

For example, a multiplex may be designed so that its outer wall sits 3 metres horizontally from HV lines, appearing compliant with clearance tables. But if workers later need to access that exterior surface for maintenance or repairs, they would be working directly at the edge of the general limits of approach—placing them within a high-risk zone. This nuance is often overlooked in project planning but is critical to ensuring long-term safety.

When Exceptions Are Considered

Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJs) recognize that strict adherence to the 3-metre horizontal clearance can, in some cases, create undue hardship for developers. In a recent conversation we had with one AHJ, they noted that alternative safety approaches may be considered where physical site constraints limit setbacks—such as an existing main house and a swimming pool restricting the laneway home footprint. In such cases, the AHJ would require a letter from the electrical engineer confirming that, while technically non-compliant, the proposed structure can still be made safe to occupy. This letter must outline additional safeguards—such as prohibiting balconies, restricting operable windows, and posting permanent warning signage at meters and overhead connection points. These measures highlight the balancing act between practical development realities and uncompromising electrical safety standards.

Lessons for Builders and Developers

These recent stop-work orders highlight three key takeaways:

- Code compliance must be verified early. Clearances should be checked at the design stage, not once construction is near completion.

- Multiple standards apply. It’s not just about the CEC—municipalities, BC Hydro, and WorkSafeBC all have enforceable requirements.

- Think beyond occupancy. Clearance planning must account for future maintenance, repairs, and worker access, not just initial construction.

At ENGVIS Engineering, we advise developers and municipalities on building placement, electrical clearances, and compliance with both utility and occupational safety requirements. As densification continues across Vancouver and other BC municipalities, overlooking these requirements risks costly delays—and more importantly, endangers worker safety.